Jean-Michel Bouhours

Jacques Riousse, the redemption of materials

Translation of the article written by Jean-Michel Bouhours in the catalogue ‘ Beautés Insensées, figures, histoires et maître de l’art irrégulier ’. The catalogue was published by Bianca Tosatti at SKIRA, Milan, Paris, pages 104-107 (2006).

The author has given his permission to reproduce his contribution.

‘Art brut is quite simply the art of the raw man,1 wrote Joseph Delteil in a magnum opus: ’Lequel serré Jean Dubuffet. He continued: ‘Which secretes its art like a snail secretes its shell, or, for that matter, like the leaves of a tree, a well-born insect or a stomach in good condition. The raw artist adopts a position that is closed in on itself, almost autistic vis-à-vis an alienating world, from which he protects himself by means of a personal symbolic system. Jacques Rousse was both self-taught and a complete artist: painter, sculptor, glassmaker and builder. More inclined towards mathematics, which he taught at a Jesuit college in Amiens, he had no artistic training and learnt the techniques that would serve him well in his career, such as electric welding and stained glass from craftsmen. Riousse learned what to do, but certainly not what to do with the materials. He was certainly a raw man in the sense in which Dubuffet defined him, that is to say, an individual whose ‘moods and impressions are delivered raw, with their very vivid smells, like eating a herring without cooking it in any way, as soon as it is caught, still dripping with sea water 2. But he was a raw man, with a mission that he had received as soon as he was released from the German prison camps, as a priest-worker. Undoubtedly inhabited by grace, Riousse produced works that attested to the divine presence. Saint Thomas wrote: ‘Let us make it clear that the perfection given to the soul by grace enables it not only to use the gift of creation, but also to enjoy the divine Person 3. Jacques Riousse shares with the other artists of Art Brut a non-referential and wild creation, untouched by any normative teaching. He has broken with society, but this break is neither ideological nor pathological, but pastoral and mystical.

The work, which I discovered only very recently 4, was at this precise moment at a turning point in its destiny. His home studio, adjoining the chapel in Saint Martin de Peille where he arrived in 1956, had just been moved. In view of the nature of the studio, all that will remain of Riousse’s work are a few pieces, still just as powerful when they leave the studio, but which will have lost their matrix universe. I was given the opportunity to visit the studio in the state it must have been in when the priest disappeared: a Spartan habitat made up of a series of small rooms in which every object had been ‘the object of his affection’: a water heater, an electric knob, a door handle, a door bore the stigmata of a creative intervention. Riousse painted, drew, glued, clumped, soldered, threaded, nailed and twisted everything within reach of his hands. It would not be a denial of the spiritual dimension of his work to assert that there was certainly a primacy of gesture, of the manuality of things. To paint, Riousse never bought a stretcher with canvas; a coarse jute canvas did the trick. As we continued our tour through the series of small, rather dark rooms that are often found in the small houses of Nice to protect themselves from the summer heat, we came to the studio, which Riousse had built himself, in the style of a favela shack, using salvaged and assembled materials. Two glass façades afforded a sumptuous view of the surrounding valleys.The studio space had been filled by an accumulation of salvaged and immediately transformed objects, finished works and materials for which it will sometimes be difficult to define a status.

The course of life is a repetition of moments, days and situations, and for humans it’s a succession of repetitive gestures, of vital needs being renewed. We produce waste, which we dispose of in such everyday, unimportant ways, because these objects are presumed to have no value or use. There are some people who have a viscerally oppositional relationship with our waste society and who reclaim it more than is reasonable. Riousse was one of these people, turning an accumulation of plastic bottles into a column of life, in the shape of a helix strongly reminiscent of the structure of DNA, which he hung above his head. Because it wasn’t enough for him to fill the floor space, the great height of the studio allowed him to hang curious objects in the third dimension, with a very Dada spirit. Here was a mobile made of wooden coat racks, reminiscent of Obstruction, a famous sculpture by Man Ray from 1920, but which Riousse had almost certainly never seen; there was a ‘cloud’, a cluster of fishing sinkers or electronic components. Machinism had inspired a new aesthetic; post-modern technologies had produced materials such as the microprocessor and the printed circuit, to which artists had shown little interest; in Riousse’s work, a printed circuit becomes the background for a Christ made of twisted sheet metal, and clusters of resistors recall both the swarm and Constant Nieuwenhuys’s utopian architecture. How can we fail to see Picasso or César in these numerous gas burners, which he probably loved for their anthropomorphic potential in his assemblages? Four welded sickles represent the tail of a cockerel: two horseshoes the body. In a white horse made from a common bicycle frame cut and turned upside down, topped with a brake shoe, we find the effectiveness of the pencil line applied to Picasso’s sculpture?

Riousse had worked as a prop maker in the film industry. In this profession, you always have to find an answer to any given situation; he had acquired a plastic gymnastics of the object. Nevertheless, both César and Chamberlain confined themselves to the world of metals: iron, painted sheet metal, copper, brass… whose forms they worked with, figuratively or abstractly. Riousse did not seem to favour any particular material or form, using iron as well as wood, plastic and discarded objects such as a bicycle frame, an electrical socket or the sole of a shoe. Every scrap seemed to be a sign. ‘I like to try everything,’ he says. He was particularly fond of fridge doors, oven trays and paint pot lids as ready-to-use picture frames. He was a junk artist 5, sharing with Rauschenberg, Wolf Vostell or Bruce Conner the same desire to work with waste taken from dustbins or public dumps. For the Americans, the choice was ideological and semiological: to work with what consumer society rejected; it was a form of protest against the presumed nobility of the artistic gesture and a neo-Dada attitude of polemical subversion. ‘To make a painting, a pair of socks is just as good as wood, nails, turpentine, oil and fabric’, declared Bob Rauschenberg in 1959. In Rauschenberg’s case, the object is integrated into a “combine painting” on the basis of its intrinsic qualities, its semiological charge and its function of use. The object used in a Riousse assemblage loses its original qualities in favour of a function of drawing form; it is immediately integrated into a signified. The artist is often figurative in his assemblages: a wheel flange represents the halo of a saint, a saw blade a jaw, buttons eyes. For Riousse, as for other artists such as Bruce Conner, the use of recycled materials is a response to economic necessity. Moreover, like Bruce Conner, he prefers materials that are in a state of refuse, that have lost the original quality of the manufactured object, and that are freed from their ‘ontological prison’.6 The materials used by Riousse are ‘washed’ of their original function and meaning, and henceforth participate in the construction of a higher symbolic order.

His Porte de Byzance is a unique assemblage of debris on a door, which was installed in the studio and had its classical functionality. Riousse assembled pieces of painted moulded wood, objects such as a kitchen scouring powder tin, discarded soaps and used soles on which he drew heads.

The work has a morbid character; each shoe still seems to bear the trace of a life gone by. But the artist has taken the idea of death conveyed by the object as a starting point, to represent the spiritual path from the bottom to the top, from death to resurrection, from decay to spiritual paradise, pointed out by these shoes and soles in ascent, on the vertical plane of the support.

The gesture of restoring the lost object has a genuine spiritual significance. It is a way of affirming the primacy of vital energy over the fate of death, of ‘renouncing the fatality of decay’.7

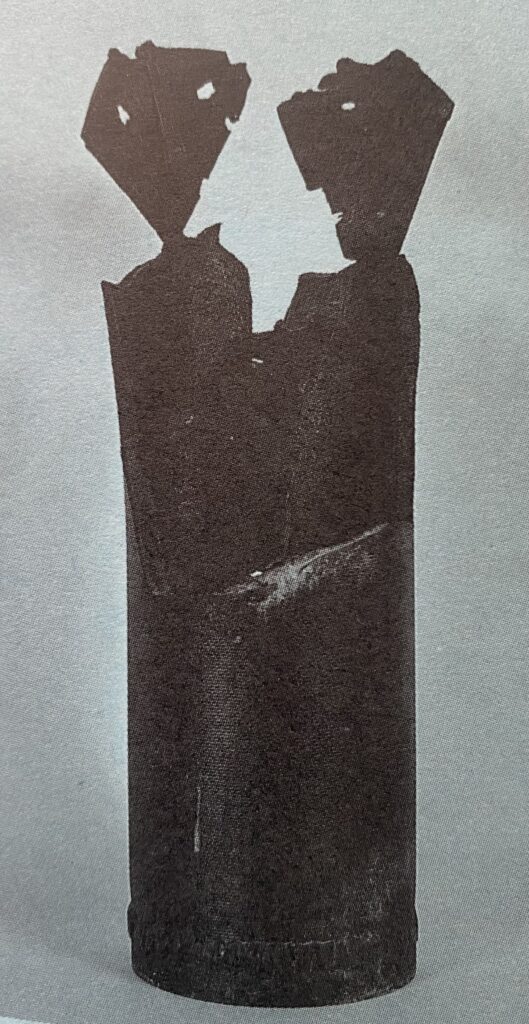

The alchemy of the artistic act transforms the ‘lead’ material destined to disappear into the sacred gold of eternity. Each time Riousse transforms one of these objects, he produces a kind of redemption of matter, an allegory of the resurrection promised by Christ. His works made with shrapnel from the last war, salvaged from the slopes of Mont Agel, above Monte Carlo, where violent artillery battles took place, demonstrate the symbolic significance conferred by the artist on the history of the material. The shattered shell – ‘a satanic explosion’ – is of course the trace of war and its destruction, both human and material; Riousse transmutes them into sacred figures: a Madonna or a Holy Family.

The Nouveaux Réalistes claimed the transcendence of reality (through the object): Riousse tends to show that divine grace is to be found, against all odds, in the most wretched object, once it has lost its homology.

Riousse’s painting is more expressionist, his sculpture Picassian or surrealist, his assemblages reminiscent of the sculptures of Karel Appel or Bruce Conner. This apparent eclecticism of style seems to represent the chaos of the contemporary world. From Art Brut, Jacques Riousse adopted the absolute freedom, the Dionysian pleasure of making, the truculence of the sharp line, but from the chaos always emerge the archetypal forms of religious sculpture and painting, because his proliferating artistic creation remained in perfect harmony with his vision of the priesthood.

Footnotes

1 Delteil J., ‘ L’homme brut ’ Cahiers de l’Herne, Paris, n° 22, May 1973, p. 166 reproduced in Abadie D., Jean Dubuffet, Paris, éd. du Centre Pompidou, 2001, p.30-31.

2 Ibid.

3 Saint Thomas Aquinas, preface and translation by R. P Mennesier, Paris, Aubier Éd Montaigne, 1942, p. 99.

4 Through Nathalie Rosticher, who showed me the chapel of Saint Martin de Peille, and then through Robert and Mireille Fillon, who introduced me to the members of the Association des Amis de J. Riousse: M. et M™* Alain Coussement, Genies Imbert and Anne Riousse.

5 This Anglo-Saxon term refers to the early work of Jasper

Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

6 Bataille G., ‘Matérialisme’ in Documents, n° 3, Paris, 1929. Quoted by R.

Krauss and Y.-A. Bois, L’Informe. Mode d’emploi. ‘Bas matérialisme’, Paris, éd. du Centre Pompidou, 1996, p. 50.

7 These words were underlined by Riousse on the leaflet for an exhibition organised in Strasbourg in 1970 entitled Récup’ Art.